Many empires have fallen before without bringing much change to ordinary lives. But then again, no empire has fallen under the eyes of a chaotic and intense media.

There is little doubt now that we are witnessing the death throes of the American empire. But this imminent collapse will not spell the end of the world. That's not to say a lot of damage won't occur as international order is reshuffled and the empire lashes out against its fate. Already, for example, the empire's leadership has spoken of a nuclear denouement to its short-lived (by imperial standards) story.

In the same way that hyperbole gripped Western media opinion in the days after the September 11 attacks, so that there was a widely agreed-upon, but far overwrought, sense that "the world changed" as a result, so too will other coming dramatic signs of imperial disintegration deliver to us, via the same hysterical media, the feeling that with the demise of the American empire, the world is ending in every sense of the word.

However, as the global British imperial system fell apart, day-to-day life changed little for its subjects. Some people found themselves in newly-minted countries, others learned their rulers were now independent of the British, and in only occasional instances did wars or rebellions break out.

Life changed for those who lived through the collapse of the Soviet empire, but only in slow, largely adaptable ways. They may have found themselves out of work, as opposed to at work but not productively occupied, but they lined up for bread all the same, now not because of a shortage of bread, but because of a shortage of money. It was a fine distinction.

This was true also for survivors of the even longer-lived Ottoman empire as it broke apart. Political leaders throughout Western Asia and the Middle East might have experienced dramatic reversals of fortune in their lives, but for the bulk of the people, they continued waking up, going to their work, eating their dinner, and going to bed, learning of the tumultuous change at the distant top of political rule only through news reports.

The final collapse of the Holy Roman empire in the mid-19th century brought about ten years of disruption to the day-to-day lives of people across Europe, but as republic administrations came to replace monarchies, much the same patterns of life resumed.

The fall of Rome, also, more than a thousand years earlier, changed life for those outside Rome in only very highly nuanced ways.

Thus it shall be for survivors of the fall of the American empire, at least for most people outside America--so long as that empire refrains from letting loose a volley of nuclear bombs in its final flickering of life that would devastate some places, and endanger the global environment everywhere else.

The one big difference between this episode of imperial collapse that we shall witness and all others that have come before, is the presence of a 24-hour-a-day instantaneous and wholly sensationalized media. Its effect on the outcome of this process cannot be over looked.

Moreover, this media--including newspapers, magazines, television networks, music producers, book publishers, and film makers--is mostly controlled from the hot centre of the empire largely by elites who, as always, stand to lose the most when empires fall. For Ted Turner, Rupert Murdoch, Conrad Black, and other titans of industry and media within the centre of the empire, the world will indeed come to an end, and perhaps in some cases literally, for lives are lost in imperial tumult.

The effect on the rest of us, however, will mostly be confusing. We will know by consulting ourselves that little has changed with the passing of the American empire, after perhaps a few years of adjustments and uncertainties. But the media portrayal of its collapse will suggest doomsday is upon us, and to the extent that we typically consult the media today more than ourselves or our neighbours, we are likely to be swept up in the breathless alarm.

A reporter who found himself by chance in an office in a building fronting on the World Trade Centre related how the workers, with a front row real-time seat to the event, had their backs to the window to watch instead the televised account of the buildings' collapse. That's as good a predictor of how we'll behave during the empire's collapse as anything else: inactive and mute, and largely unaffected spectators, nonetheless swept up into the alarm perpetrated by the media more than the alarm our own senses might register.

Political power derives almost entirely from the collective power of persuasion among leaders. In other words, political authority is maintained only so long as people generally believe political authority is maintained. All avenues of mainstream media are instruments of persuasion firmly in the hands of leaders, which is the entire point of owning media. (One need only recall National Post newspaper owner Israel Asper's comments last month regarding his objectives, as owner, in projecting through his newspaper's coverage of news a pro-militant Israel point of view. About making a profit, he was silent. The paper has, so far, lost $300 million).

The prime objective of media during the collapse of the American empire will be to dissuade people from the view that the empire is collapsing. After all, it is the owners of media who today form part of the elite of authority in the empire, and if people were led to think the empire is collapsing, they will also imagine existing authority is breaking down, which it will just as soon as people think it is.

Therefore, the biggest news story of the last 200 years--the collapse of the American empire--will go wholly unreported. Worse yet, as the leaders of that empire ascertain their coming demise, they will over-react, and share their over-reaction through their media with us all, so that we'll all be put into the state of their panic, even while it is only they, and not us, who have any reason to fear the coming changes. Our confusion and fear will be exacerbated because, unlike people who have lived through imperial collapses in the past, we are fully saturated in the elites' media, and mistrust our own senses.

Medieval kings asked that the people identify themselves with the kings' actual physical bodies in order that the people would feel that a threat to the life of the king, or even just a threat to the king's property or capital, would be felt by the people as though it were a threat to their very own lives or to their very own property. Thus would the people sign themselves (or their sons) up to willingly go and risk their lives in wars or crusades in defence, actually, of only the king's life or property, while the king would hide himself and his family and entourage safely away from any trouble, as long as trouble lasted.

The kings managed this trick through the instrument of the media, such as it was in medieval days. Then, it might have been messengers on horseback riding from village to village to warn of the looming catastrophe or spread news of the booty available. Today, cablevision and newspapers serve the same purpose. Thus, US President George Bush, in September of 2001, was quick to announce, after emerging from hiding after the immediate trouble passed, that the attack was not to be seen as box cutter-wielding hijackers steering planes into office buildings, but rather as an attack by hatred against freedom.

Those at risk were not him and his cabal, but every one of the ordinary working class citizens. Iraq and Iran, similarly, are not to be seen as nations contesting the mostly American corporate elites' monopoly over energy supplies, but rather as "evil" entities threatening the American way of life--which is defined vaguely as "liberty" and "freedom." Americans are dutifully signing up their sons to go fight a foreign war to protect the elites' property investments and energy supplies, but under the impression they are out to defend freedom and battle evil.

There is reason for bitter reflection upon the demise of the American empire, to be sure. America at one time legitimately represented a beacon of hope for self-government in a world, at the time, largely governed by self-appointed elites. The American Revolution did succeed in replacing an overly taxing British regime with a home-spun authority that kept tax revenues on the side of the Atlantic ocean from which they had been raised. It also propelled forward, in a limited way, the evolving notion of political authority drawn from among the common people over whom authority was to be exercised. The resulting economic success of America provided a model for the rest of the world, who accurately saw in the principle of self-government the key to improved health, happiness, and prosperity.

America, however, has departed by now far from the principle of self-government, so that the old catch-phrase that neatly captured the spirit of the principle, "Anyone could someday be President," is now nothing but a joke. The illegal US Supreme Court appointment of George Bush as President, over the wishes of the majority of voters who elected Al Gore in the fall of 2000, is only a blunt illustration of what's been the case for several generations in America by now.

It is unfortunate, then, that the failure of America, brought on by the fact that political authority there has long been usurped by illegitimate elites, will instead be inaccurately blamed on the principle of self-government that America once represented, long ago, but no longer does today. The tragedy that looms before us is not found in the coming collapse of the American empire, which is an event that can only be welcomed, but is instead found in the coming collapse of the American ideal, which will take several generations to rebuild all over again.

Then again, the time for weeping over America's loss of its ideal is long passed--that has already happened, and is a long-closed chapter in that nation's history, just as Rome once represented laudable ideals, but evolved later into a machine intent on subverting them.

But it may be possible to hope that the ideal America once represented was successfully transplanted to elsewhere in the world, and among saplings of the once mighty but now fallen oak, root has taken, and limbs have grown forth. After all, that ideal--freedom, happiness, and prosperity as the fruit of self-government--pre-dates America, and there is no reason to think it won't post-date America as well. The ideal, in other words, may survive the death of the nation that for a time hosted it, and permitted, for a time, its further evolution.

Almost all nations that grew into empires did so because, in their infancy as great powers, they embodied noble ideals of one kind or another. It is also true that each empire then grew to subvert those very ideals that gave it its fuel in the first place. And it is more the truth in all history that the fall of the corrupted empire was a necessary pre-condition for those ideals to find new and re-invigorated root elsewhere--just as old and too-large trees are required to fall before new trees can find light out of the cleared forest canopy, and sustenance out of the rotting, fallen log.

The imminent fall of the American empire will occasion a series of distressing events made all the more worrisome by the 24-7 media coverage of it. But as thunderous and ground-shaking as the fall of the forest's biggest tree can be, it is important not to lose faith during the tumult, confusion, and fear that, after the dust settles, a new beginning will come. The American empire will fall with a fearsome and terrible noise. Nonetheless, it is a welcome event, and one to be yearned for. Even hastened.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

About Me

- cobra@cobravstheworld.com

- Killadelphia, Pa, United States

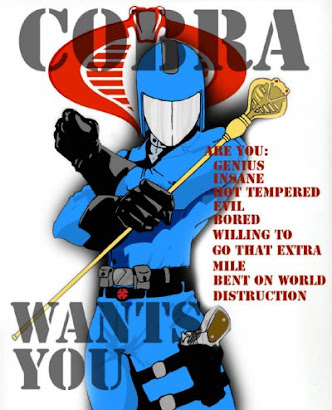

- Absolute power! Total control of the world... its people, wealth and resources - that's the objective of Cobra Commander. This fanatical leader rules with an iron fist. He demands total loyalty and allegiance. His main battle plan, for world control, relies on revolution and chaos. He personally led uprisings in the Middle East, Southeast Asia and other trouble spots. Responsible for kidnapping scientists, businessmen and military leaders, then forcing them to reveal their top level secrets. Cobra Commander is hatred and evil personified. Corrupt. A man without scruples. Most dictators and would-be Napoleon types are hampered by the need to pretend that they are pursuing a noble and just cause. Cobra Commander doesn't have that problem. This guy's in it for the money and the power, and if anybody else is interested in these things, they can pick up an assault rifle and get in line behind him.

Links

- WWW.COBRAVSTHEWORLD.COM

- Cobra Commander @ Myspace.com

- Cobra Commander @ Facebook.com

- Glory Hole Girlz

- Tampa Bukkake

- Cock Sucking Championship

- Crack Whore Confessions

- Electricity Play

- Gang Bang Hood

- Ghetto Confessions

- Party Wild Naked

- Phoenixxx Blaque

- Porn Video Drive

- Real Orgasm Videos

- Skunk Riley

- Slut Wife Training

- The Oral Slut

- The Stall

- Theater Sluts

- Ukrain Amateurs

- Young Busty

- Club Seventeen

- Seventeen Live

- Seventeen Video

- TeensfromTokyo

- Old Farts Young Tarts

- My Sexy Kittens

- Retro Raw

- Rodox

- UK Roadtrips

- Excuse me

- Jim Slip's Ukstreetsluts

- Top Cams

- Beauty And The Senior

- Clubseventeen (Norwegian)

- Glossy Angels

- Spunky Teens

- Barely Evil

- Gothic Sluts

- Rubber Dollies

Blog Archive

-

▼

2008

(1069)

-

▼

February

(92)

- Don't panic, it's only the end of the American Empire

- David Simon on the End of the American Empire

- Merton's Strain Theory

- Feudalism vs. Democracy

- Occultism

- .........

- ................

- .............

- The Dark Side

- .................................

- ..............

- Original Sin

- The Hero

- my girl shakin booty

- Dancing, shakin booty!

- MORE BOOTY!!

- booty in a thong!!

- ass shakin booty poppin

- Intro

- Bounce

- spongebob

- Smooth Operator!

- Windin

- Dancin In a new party clothes

- Pretty Willie......touchin it.

- do you love it

- DANGER1

- one mo

- that deal ass part#2

- 2 Much Booty N Dem Pants

- Booty Meat

- booty meat

- she gotta donk 2

- Big Juicy Back

- petite and bouncy coed dancing

- Naughty College Girl in Panties

- Wild Booty Shaking and Vibrating 2

- athletic teen shows off

- latina wants it bad

- dancin

- Latina booty dancing pt 2

- Slender Latina Booty in the Air

- Naughty College Girl in Panties again

- Wild Booty Shaking and Vibrating

- BUMPER REMiX

- bull riddin in rosarito

- two white girls booty

- cute teens panties dancing

- Hot ass Shaking

- Nice Booty Shake

- booty popping

- Bootylicious Nikki - Sexy girl Booty Dance

- Tshirt and Panties Booty Dance HOT

- angel's booty meat

- ...

- .............

- The Ghetto Matrix

- ...........................

- .............

- ....

- ..........

- ..........

- ..................

- ................

- ....

- ............

- Knights of Malta

- .................................

- .....................

- .........

- ..

- .......

- ........

- .......

- ...................

- Freemasonry

- Break It Down(Sissy Nobby)

- Back Dat Azz UP!!

- SHE GOT A DONKEY!!

- ........

- Feist - 1234 (GREAT QUALITY!!)

- Feist - 1234 (Director's Version)

- Sex and the Paranormal

- ..

- ........

- The Extraterrestrial Conspiracy

- Gorillaz - Clint Eastwood

- Spanish Neighbors

- Dirty Dentist

- ...................................

- ......

- ................

-

▼

February

(92)