Mayor Street inspected the troops at the 12th Police District roll call for the cameras yesterday afternoon and announced a plan to flood the streets of violence-plagued Southwest Philadelphia with officers and social services.

What Street did not mention, until asked by a reporter, was the recent rash of violence inside city schools.

"We are going to be very aggressive. . . . When you make things better in the community, you have an impact on children and violence," he said in response.

Before yesterday, Street had made few, if any, public comments about school mayhem since a pair of students broke a teacher's neck at Germantown High School nearly three weeks ago.

This week, students assaulted at least four teachers in district schools, and there were seven attacks at West Philadelphia High alone over the last 10 school days. The issue has dominated nightly newscasts and appeared on newspaper front pages.

The mayor's relative silence on the issue of battered teachers stands in stark contrast to the badgering he gave schools chief Paul Vallas late last year over the district's $73.3 million budget deficit.

Then, Street spent nearly 14 hours over four days sitting in the front row during public hearings on the fiscal problems, interjecting his criticisms. He also testified before City Council on the issue.

In some ways, aides say, the disparity arises from Street's leadership style: He's no Rudolph Giuliani-style tub-thumper, preferring to tinker with the machinery of government rather than exhort the public - and grab headlines - through the mass media.

The Street administration has launched a $3 million program to hire more truancy officers and also is establishing 12 curfew centers that will give youths safe havens from the streets. Education Secretary Jacqueline Barnett also participated in a March 6 meeting with Vallas and Police Commissioner Sylvester M. Johnson that spelled out a tough new security policy for schools.

"The mayor takes a systems approach," Barnett said. "For him it's how do you get at the root of the chronic social issues we have. He's absolutely passionate about it."

But some continue to wish Street displayed that fervor more often in public.

"The mayor can use that bully pulpit for folks to rally around," said State Rep. Dwight Evans, a candidate in the Democratic mayoral primary, who has developed programs in Harrisburg to combat youth violence.

"Neither the school district nor the city government can do it by themselves," Evans said, adding that Street deserves credit for some of his policies. "In my view, the mayor can speak to the issue, to say we've all got to be responsible for the schools."

Street has often clashed with Vallas since Harrisburg took over the school district in a 2001 deal that brought more state funding. State control constrains the mayor's ability to act, but there could be better coordination, some say.

"I've been on six committees, urging more collaboration between schools and the city," said Shelly Yanoff, executive director of Philadelphia Citizens for Children and Youth. "Everybody talks the talk, but it's hard. We need to get the resources there and really do require the coordination, the city and the schools really coordinating their resources and implementing plans that make sense."

Evans said "better relationships" among the mayor, the police commissioner, and the schools chief would help, adding that a mayor with a big-picture perspective could highlight the need for more parental responsibility and help support that.

And Ellen Green-Ceisler, the consultant who produced a study finding disarray in the school discipline system, said that the mayor could have a huge impact by ruthlessly assessing the multiple contracts the city has with nonprofits to provide social services in the schools.

"Who's monitoring these contracts - are they any good?" Green-Ceisler said. "I didn't see enough evaluation of that. . . . With the limited resources, we absolutely can't afford to have these contracts going to programs that are not working."

One point of contention between the school leadership and Street is unlikely to change. Vallas has said he would like to put armed Philadelphia police officers at district high schools, but Street has rebuffed the idea.

Currently, only school district police are stationed in school buildings. The officers have arrest powers but no guns.

Even in the wake of a rash of violence in city public schools, Barnett, Street's secretary of education, said revisiting the issue was a nonstarter.

"The administration will not consider armed officers in schools," Barnett said.

Street's position has been that guns are not an appropriate deterrent, and that parents do not want armed officers around their children. Johnson has agreed, saying he does not want to make school buildings "armed penitentiaries."

Some large districts, including Chicago, Los Angeles and New York, have armed officers in schools. And some smaller ones - especially those that have faced violence - make the same decision. Locally, Camden and Chester are examples.

Barnett said the issue also needs to be examined in context of the students' complex home lives.

"It is never acceptable to strike or attempt to harm a teacher, but we need to be mindful of some of the emotional baggage students are coming to school with," she said.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

About Me

- cobra@cobravstheworld.com

- Killadelphia, Pa, United States

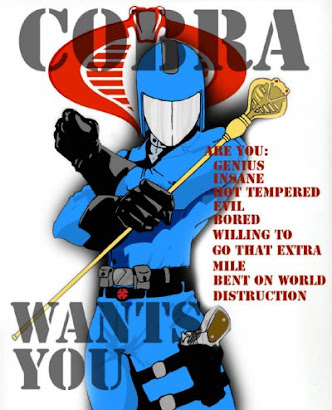

- Absolute power! Total control of the world... its people, wealth and resources - that's the objective of Cobra Commander. This fanatical leader rules with an iron fist. He demands total loyalty and allegiance. His main battle plan, for world control, relies on revolution and chaos. He personally led uprisings in the Middle East, Southeast Asia and other trouble spots. Responsible for kidnapping scientists, businessmen and military leaders, then forcing them to reveal their top level secrets. Cobra Commander is hatred and evil personified. Corrupt. A man without scruples. Most dictators and would-be Napoleon types are hampered by the need to pretend that they are pursuing a noble and just cause. Cobra Commander doesn't have that problem. This guy's in it for the money and the power, and if anybody else is interested in these things, they can pick up an assault rifle and get in line behind him.

Links

- WWW.COBRAVSTHEWORLD.COM

- Cobra Commander @ Myspace.com

- Cobra Commander @ Facebook.com

- Glory Hole Girlz

- Tampa Bukkake

- Cock Sucking Championship

- Crack Whore Confessions

- Electricity Play

- Gang Bang Hood

- Ghetto Confessions

- Party Wild Naked

- Phoenixxx Blaque

- Porn Video Drive

- Real Orgasm Videos

- Skunk Riley

- Slut Wife Training

- The Oral Slut

- The Stall

- Theater Sluts

- Ukrain Amateurs

- Young Busty

- Club Seventeen

- Seventeen Live

- Seventeen Video

- TeensfromTokyo

- Old Farts Young Tarts

- My Sexy Kittens

- Retro Raw

- Rodox

- UK Roadtrips

- Excuse me

- Jim Slip's Ukstreetsluts

- Top Cams

- Beauty And The Senior

- Clubseventeen (Norwegian)

- Glossy Angels

- Spunky Teens

- Barely Evil

- Gothic Sluts

- Rubber Dollies

Blog Archive

-

▼

2008

(1069)

-

▼

March

(790)

- ............

- Papoose - Ambulance Video

- papoose

- Papoose-Alphabetical Slaughter

- Lil Wayne Backyard Interveiw

- MANORbOYRAGE- bOOTY ROll

- MANORbOYRAGE-POP iT LikE A POP-TART

- she got a donk.

- POST UP

- Booty Meat www.myspace.com/youngcherrys

- SHE GOT A DONK!! www.myspace.com/youngcherrys

- white girl got ass

- in grey booty shorts

- wowz

- New Orleans Bounce --Cali Misses Chedda Chedda--

- New Orleans Bounce

- Girls Gone Wilder - Black Booty Edition "cuffs"

- girls gone clubin "sexy shakin"

- girls gone clubin "nasty nights"

- girls gone clubing "Night vision"

- BOOTY CONTEST

- ICEbunny Shakin Somethin Solid

- ICEbunny Booty Shakin Pt2

- booty meat

- Amazing big ass!

- Sensual booty

- Amazing booty on cam

- booty shakin

- Headache

- booty booty

- tiny tiny tiny tiny tiny preview of whats coming =]

- dont laugh = P

- me dancing (tired lol)

- JEJE

- club girls

- DALLAS BOOTY

- BOOTY CONTEST

- .........

- ................

- Fat Joe - 300 Bolic / Crack House BRAND NEW

- Fat Joe - 300 Brolic

- Fat Joe - 300 Brolic (Movie Version)

- ass

- jacked

- thick one

- jacked!!

- mzjae

- big girl ass

- Hot Booty Shaking

- Booty poppin

- POPPING MY BOOTY

- lovin that mia music!!

- shaking it up - Bounce Bounce

- Hot Booty Shaking

- me, big sis and auntie booty battle

- big girl ass 2

- me booty shakin

- jacked!!

- jacked

- Phat ass in Ecko Sweats

- Big booty at Taco Bell! Her ass was so fat! sexy ass!

- street bake

- big booty walking in jeans

- ...................

- ............

- ..........

- ................

- bojangles

- 2 girls in short shorts

- booty bounce 4

- HOLLYWOOD....[ATL]....TIERRE

- Dipset the Movie

- Military strategies

- Routines Military Workout

- U.S. Army HOOAH 4 HEALTH Fitness - Toning Exercises

- Cardio Boot Camp

- Killarmy

- Lord Finesse vs Percee P

- DAAAAAAAAAAAAAAM

- booty

- us

- white chocolate the other onee

- white chocolate

- ass shaking

- drop and give me 50

- April a.k.a Chewy Dancing drop and Give me 50

- ...........

- Tempers, guns key to child deaths

- Investors' plans ruined by flood

- James M. Reif Jr: Driven by life's endless possibi...

- Phils hear from group on violence prevention

- At W. Phila. High, a call by students to settle down

- S.W. Phila. gets show of force

- As violence flares in schools, Street is a man of ...

- Girl hits principal at N. Phila. school

- New unrest, plans for W. Phila. High

- West Philadelphia students speak out

- Two men create a memorial to lives taken in city v...

- 3 shootings kill mother, man, wound 2 girls

- Brother, husband arrested in death

-

▼

March

(790)